page 3 of 20

Inside the Neligh Mill

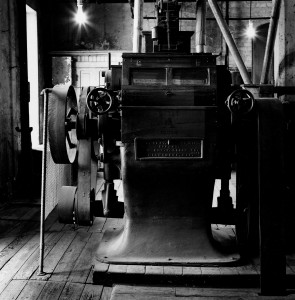

An old mill is built like a well ordered day; it tackles the hardest task first—lifting grain to the top of the building—then lets gravity and a little flywheel momentum do the rest. The river could gin this action all day long, coasting through most of it. Once lifted and binned, the wheat was dropped through elevator legs into various stands of equipment. The mill’s three floors and basement are literally jammed with equipment, edge-to-edge. The first floor did the grinding and sacking, the second floor the sorting, purifying, bleaching and dust control—grain dust is explosive—and the third floor the steaming and sifting. Steam toughened the hulls a bit, causing the kernels to shatter into larger pieces, which improved efficiency. The sifting was done through vibrating silk screens and coarse linen flutes.

An old mill is built like a well ordered day; it tackles the hardest task first—lifting grain to the top of the building—then lets gravity and a little flywheel momentum do the rest. The river could gin this action all day long, coasting through most of it. Once lifted and binned, the wheat was dropped through elevator legs into various stands of equipment. The mill’s three floors and basement are literally jammed with equipment, edge-to-edge. The first floor did the grinding and sacking, the second floor the sorting, purifying, bleaching and dust control—grain dust is explosive—and the third floor the steaming and sifting. Steam toughened the hulls a bit, causing the kernels to shatter into larger pieces, which improved efficiency. The sifting was done through vibrating silk screens and coarse linen flutes.

—

Machinery like this is so simple and substantial that it can almost run itself. It would have needed a miller, of course—the lone aristocrat in such a palace—who’d serve as line mechanic. He may have had an assistant, who in the early years, would have doubled as water tender. All other workers would have been sackers, sack sewers, stackers, cart runners and occasional rail-car jackers—lifters and luggers all. In the booming 1920s, the mill employed 30 such men in two 12-hour shifts. This would have been numbing work, the original “daily grind,” with a steady depletion of cartilage all around. There were quotas, so they would have hustled. Today this would be immigrant work, as some of it must have been then. When you make a career of lifting, it helps to remember the old country, to see your spawn as teachers and nurses and insurance men, and theirs as doctors and lawyers and scientists, all ambitious and forthright and beyond the taint of accent. Generations would stand on your shoulders, or so you’d imagine, and your days would use you up.

What were these workers like? It’s almost too late to know, but some of us could round up characters from other menial jobs to raise a crew. There’d be a braggart, of course, a profligate. There’d be a brooder, a sports nut and a love-sick boy. The boy would suffer rude inquiries. There’d be a wormy little ass kisser, a former school-eraser clapper. There’d be two practical jokers, because these only come in pairs. There’d be a pain-in-the-ass proselytizer, the victim of practical jokes. There’d be the guy who makes a pathology out of shortness or baldness or both. There’d be missing fingers, each a cautionary tale. One guy would talk too much, say too little, another would cling to his Thermos. There’d be a wisecracker, a loud and likeable sort, who’d fold and retreat when he laughed, an arm across his mouth. There’d be an old fart, a young Turk, a grass-is-greener window gazer. The old timer, in his fifties, would wear copper wire around his wrists to hold arthritis at bay. He’d slather his shoes with mink oil and tell you about it. Ask him for the time, and he’d say, “Why, you takin’ medicine?” And there’d be that one obligatory character, whose sexual euphemisms are so hilariously precise, that years later you’d find yourself cracking up, owing apologies.